Emily Dickinson va néixer a Amherst (Massachusetts) el 10 de desembre del 1830 i hi va morir el 15 de maig de 1886. Des de molt jove va viure tancada en el seu món. Escriure cartes era la forma amb què establia vincles amb la mateixa realitat de la qual s’allunyava. En vida no va publicar gairebé res. La seva poesia va veure la llum pòstumament gràcies al seu mentor literari, T.W. Higginson, i va obtenir un èxit immediat. Avui se la considera la millor poeta americana del segle XIX.

Quan tenia 31 anys, i després d’haver llegit un article de T.W. Higginson en un diari, Emily Dickinson va gosar enviar-li uns dels poemes que havia escrit. A Higginson li van agradar tant que va demanar-li que li expliqués com era la seva vida, i es va iniciar així una fructífera correspondència entre tots dos. La poeta va respondre amb una carta que, igual que el seu poema Jo no soc ningu. Qui ets tu?, reproduïm en anglès i en la traducció catalana.

Foto: Special Collections at Amherst College

Jo no soc ningú. Qui ets tu?

Jo no soc ningú. Qui ets tu?

Ets tu, ningú, també?

Som nosaltres, ja, un parell?

No ho diguis! Ho anunciarien, saps?

Que lúgubre, ser qualcú!

Que públic, com la granota

Dient el seu nom, tot el sant juny

A una bassa embadalida!

(Traducció de Joan Cerrato)

I’m Nobody! Who Are You?

I’m nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there’s a pair of us — don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

Mr. Higginson,

La seva amabilitat exigia una resposta més ràpida, però vaig estar malalta i li escric avui, des del meu coixí.

Moltes gràcies per l’anàlisi quirúrgica, no va ser tan dolorosa com em pensava. Li faig arribar altres poemes, tal com em demana, encara que és possible que no siguin gaire diferents. Mentre el meu pensament està despullat els puc distingir, però quan està vestit em semblen tots iguals i adormits.

Em preguntava quants anys tinc. No he escrit poemes, tret d’un o dos, fins aquest hivern, senyor.

Tinc una por des del setembre, que no puc explicar a ningú, per això canto, com ho fa el noi al costat del cementiri, perquè estic espantada.

Em demana pels llibres. Com a poetes, tinc Keats, i el senyor i la senyora Browning. En prosa, el senyor Ruskin, el senyor Thomas Browne i l’Apocalipsi. Vaig anar a l’escola però, en la seva manera de dir-ho, no he tingut una educació. Quan era una nena petita, un amic em va ensenyar la Immortalitat, però aventurant-s’hi de massa a prop, no va tornar mai més. Poc després el meu tutor va morir i, durant bastants anys, el lèxic va ser el meu únic amic.

Em pregunta pel meus companys. Els turons, senyor, i la posta de sol, i un gos, que el meu pare em va comprar, que és tan gran com jo. Els gossos són millors que els humans, perquè saben però callen i el soroll de l’estany al migdia és millor que no pas el meu piano.

Tinc un germà i una germana, la mare no dona importància al pensament, i el pare està massa ocupat amb els seus escrits per adonar-se del que faig. Em compra força llibres però em suplica que no els llegeixi perquè té por que em facin trontollar la ment. Ells són religiosos, excepte jo, i cada matí s’adrecen a un eclipsi a qui anomenen “Pare”.

Tinc por que la meva història el cansi. M’agradaria aprendre. Em podria explicar com puc créixer, o no es pot dir, com si es tractés d’una melodia o de la bruixeria?

Em parla sobre Mr Whitman. No he llegit el seu llibre, però m’han dit que és vergonyós.

Vaig llegir Circumstances de Miss Prescott, però em perseguia en la foscor, així que l’he evitat.

L’hivern passat dos directors de diaris van venir a casa del meu pare preguntant-me pels meus pensaments, i quan els vaig respondre “per què?” em van dir que era miserable i que ells els farien servir arreu.

No sóc capaç de valorar-me a mi mateixa. La meva mida em sembla tan petita. Vaig llegir els seus articles a l’Atlantic i vaig sentir admiració per vostè. Estava segura que no rebutjaria una pregunta de confiança.

És això, senyor, el que em va demanar que li expliqués?

La seva amiga,

E. Dickinson

Versió original

Mr Higginson,

Your kindness claimed earlier gratitude but I was ill and write today, from my pillow.

Thank you for the surgery; it was not so painful as I supposed. I bring you others, as you ask, though they might not differ. While my thought is undressed, I can make the distinction; but when I put them in the gown, they look alike and numb.

You asked how old I was? I made no verse, but one or two, until this winter, sir.

I had a terror since September, I could tell to none; and so I sing, as the boy does by the burying ground, because I am afraid.

You inquire my books. For poets, I have Keats, and Mr. and Mrs. Browning. For prose, Mr. Ruskin, Sir Thomas Browne, and the Revelations. I went to school, but in your manner of the phrase had no education. When a little girl, I had a friend who taught me Immortality; but venturing too near, himself, he never returned. Soon after my tutor died, and for several years my lexicon was my only companion.

You ask of my companions. Hills, sir, and the sundown, and a dog large as myself, that my father bought me. They are better than beings because they know, but do not tell; and the noise in the pool at noon excels my piano.

I have a brother and sister; my mother does not care for thought, and father, too busy with his briefs to notice what we do. He buys me many books, but begs me not to read them, because he fears they joggle the mind. They are religious, except me, and address an eclipse, every morning, whom they call their “Father.”

But I fear my story fatigues you. I would like to learn. Could you tell me how to grow, or is it unconveyed, like melody or witchcraft?

You speak of Mr. Whitman. I never read his book, but was told that it was disgraceful.

I read Miss Prescott’s Circumstance, but it followed me in the dark, so I avoided her.

Two editors of journals came to my father’s house this winter, and asked me for my mind, and when I asked them “why” they said I was penurious, and they would use it for the world.

I could not weigh myself, myself. My size felt small to me. I read your chapters in the Atlantic, and experienced honor for you. I was sure you would not reject a confiding question.

Is this, sir, what you asked me to tell you? Your friend,

E. Dickinson

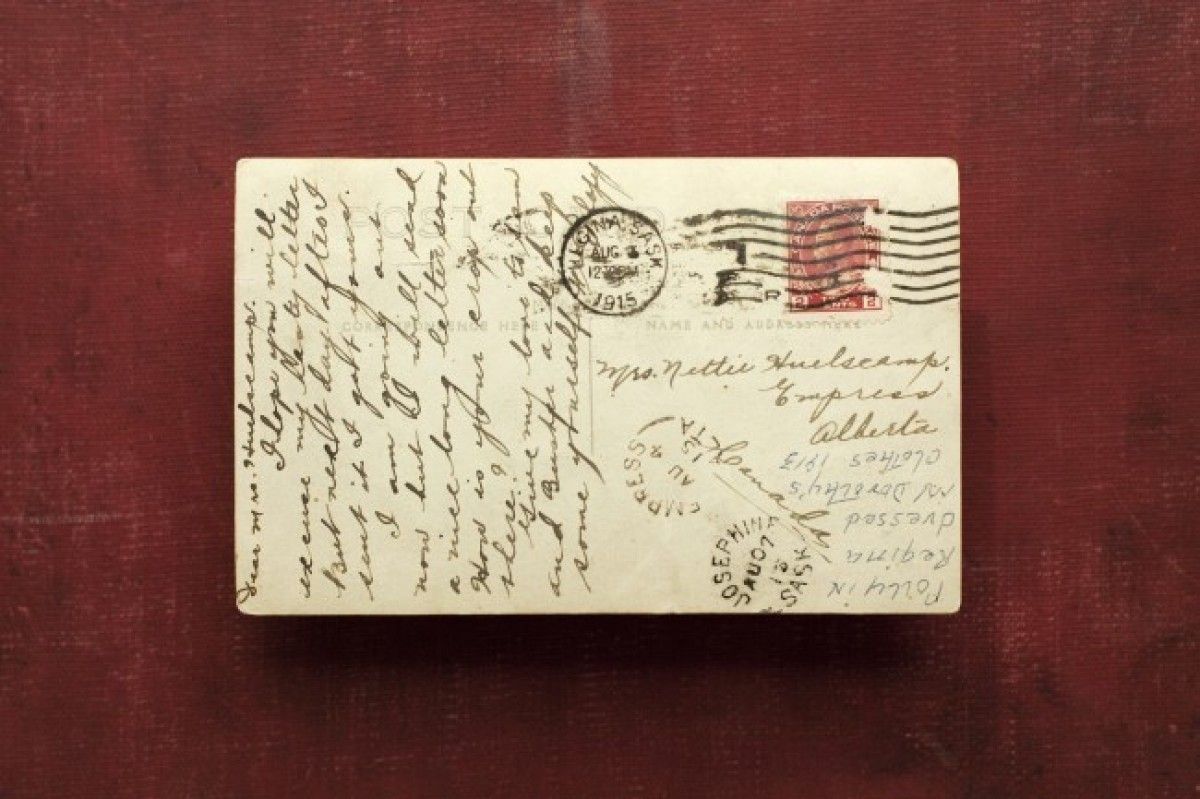

Foto: Grant Hutchinson