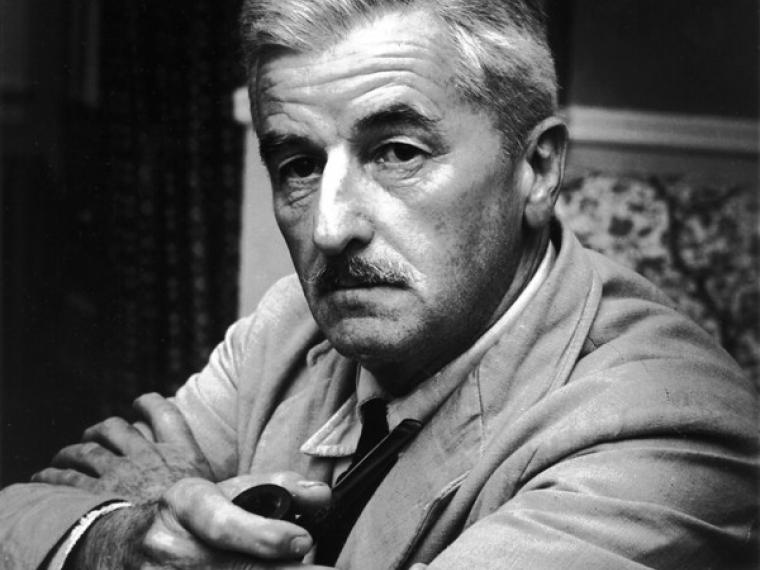

L'escriptor William Cuthbert Faulkner (25 de setembre del 1897, Mississipí – 6 de juliol del 1962, Mississipí) va ser guardonat amb el Nobel de literatura l'any 1949. Escoltem i llegim el discurs (en català i en anglès) que va fer en rebre aquest reconeixement a Estocolm el 10 de desembre del 1950.

Senyores i senyors,

Sento que aquest premi, més que donar-me'l a mi com a home, s'ha donat a la meva obra –l'obra de tota una vida entregada a l'agonia i les preocupacions de l'esperit humà, no per glòria ni per treure'n un profit econòmic, sinó per crear, a partir dels materials de l'esperit humà, alguna cosa que abans no existia. De manera que aquesta distinció se m'ha donat per una qüestió de confiança. No serà difícil trobar una dedicació perquè la part monetària que comporta estigui d'acord amb els elevats propòsits i significats del seu origen. Però també m'agradaria fer el mateix amb l'aclamació, utilitzant aquest moment com un lloc des d'on potser m'escoltin nois i noies que ja es dediquen a la mateixa angoixa i treball que jo, entre els quals ja es troba aquell que un dia estarà dret aquí on soc ara.

La nostra tragèdia d'avui és una por psicològica general i universal que ha estat sostinguda durant molt de temps fins ara, que fins i tot podem suportar-la. Ja no existeixen els problemes de l'esperit. Només ens queda una pregunta: quan seré esclafat? És per això que els nois i les noies que avui escriuen han oblidat els problemes del cor humà que està en conflicte amb ell mateix, quan només d'això podran fer bona literatura perquè és l'únic tema del qual val la pena escriure, i que en justifica l'angoixa i la suor.

L'escriptor jove ha d'aprendre-ho de nou. S'ha d'ensenyar a si mateix que la màxima debilitat és estar espantat, i després d'ensenyar-s'ho a si mateix, ha d'oblidar-ho per sempre, sense deixar cap mena d'espai al seu lloc de treball per res que no siguin les antigues realitats i veritats del cor, les antigues veritats universals sense les quals tota la història és efímera i està predestinada al fracàs: l'amor i l'honor, la pietat i l'orgull, la compassió i el sacrifici. Fins que no ho faci, continuarà treballant sota una maledicció. No escriurà d'amor sinó de luxúria, de derrotes en què ningú perd res de valor, de victòries sense esperances i, el pitjor de tot, sense pietat ni compassió. Les seves penes no s'escaparan cap als ossos dels altres, no deixaran cicatrius. No escriurà sobre el cor sinó sobre les glàndules.

Fins que no torni a aprendre aquestes coses, continuarà escrivint com si estigués entre els altres i observés el final de l'home. Declino acceptar el final de l'home. És prou fàcil dir que l'home és immortal simplement perquè perdurarà: que quan hagi sonat el darrer timbre de la destrucció i el seu eco s'hagi esvaït entre les últimes roques inservibles que deixa la marea en el darrer vermellós i moribund vespre, encara llavors s'escoltarà un altre so: el de la veu dèbil i inextingible de l'home, encara parlant.

Em nego a acceptar això. Crec que l'home no només perdurarà: prevaldrà. Crec que és immortal no per ser l'única criatura que té una veu inextingible, sinó perquè té una ànima, un esperit capaç de ser compassiu, de sacrificar-se i de tenir perseverança. El deure del poeta i de l'escriptor és escriure sobre això. Aquest és el seu privilegi: ajudar l'home a mantenir-se alçant el cor, recordant-li el coratge i l'honor i l'esperança i l'orgull i la compassió i la pietat i el sacrifici que han sigut la glòria del seu passat. La veu del poeta no ha de relatar simplement la història de l'home, sinó que pot ser un dels puntals, els pilars que l'ajuden a resistir i prevaler.

Ladies and gentlemen,

I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work –a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will some day stand here where I am standing.

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed – love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking.

I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.